This article was originally published in Bloomberg Tax.

Online shoppers in the US often skip providing their full names or addresses when buying digital products such as e-books or video games. It’s a common oversight, as not all retailers require this information to complete purchases, but it can wind up creating challenges when it comes to collecting and remitting sales taxes.

The rise of digital goods—including games, movies, music, and non-fungible tokens—has led to tax-sourcing issues, particularly when retailers use payment platforms that don’t collect all the customer information necessary for tax calculations. A particular pain point comes when sellers only collect a customer’s five-digit ZIP code, rather than the more precise nine-digit code, making it more difficult for retailers to figure out the correct taxing district, such as a city or county boundary. States have argued that this level of detail would help retailers determine which jurisdiction to assign a digital sale to, especially in states that have combined sales tax rates.

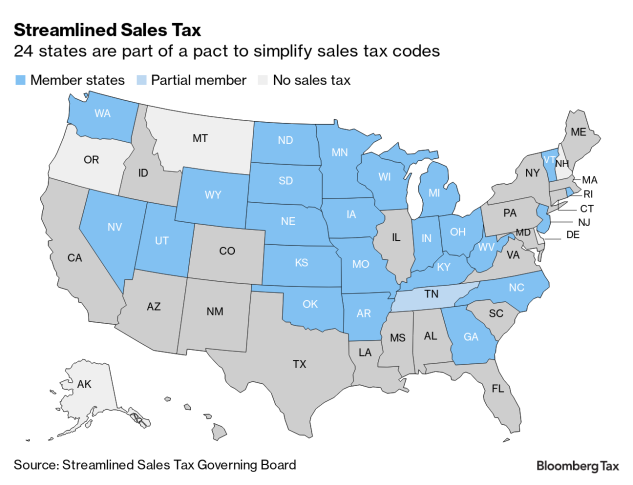

Some interstate tax groups have tried to address these sourcing issues, but progress is slow. The Streamlined Sales Tax Governing Board, which administers a 24-state pact to simplify sales tax codes, has spent two years on a project that’s been delayed by disagreements among states, localities, and corporations. The business sector has argued that more data collection represents an additional administrative burden, while sellers collecting and retaining personally identifiable information could be impacted by states’ consumer data privacy laws.

“There are some states that say, ‘No, we need the full address’, and that’s pretty tough for some of these businesses to take,” said Mike Bailey, a former Government Finance Officers Association board member who is part of the Streamlined work group addressing the sourcing dilemma. “We have to see if some of the states are in that particular position, or if they are willing to look at alternatives. Because of that, we’ve been around the same points of disagreement on this for the past few years.”

Two Years, Little Progress

Streamlined has spent two years attempting to craft guidelines on transaction sourcing when a seller collects only five-digit ZIP codes and other partial customer information, and how that should determine what sales tax retailers should collect from their customers inside a given ZIP code.

According to a draft proposal discussed at Streamlined’s annual meeting last week in Louisville, Ky., a state could choose one of three options: the lowest rate, the highest rate, or a blended rate. Members of Streamlined’s business advisory council argued that applying anything higher than the lowest rate would be “a discriminatory tax on electronic commerce barred by the Internet Tax Freedom Act.”

Streamlined’s governing board voted on Nov. 8 to send a draft back to the work group with three directives: Focus exclusively on digital transactions that don’t need physical delivery; suggest, rather than mandate, that states require full addresses or nine-digit ZIP codes for these sales; and allow states to set tax rates for digital sales while recording five-digit ZIP codes in a database.

This new approach diverges from initial state requests that retailers collect full addresses, but the work group may reach a compromise by asking for the collection of nine-digit ZIP codes from retailers that don’t gather complete addresses from their customers.

While states have argued that retailers must collect all information for accurate tax calculation, the business community has resisted mandates requiring complete street addresses, especially if such information isn’t needed to complete a sale.

Several issues will remain unresolved if Streamlined’s sourcing project doesn’t move forward, Bailey said. Businesses that aren’t complying with sales tax laws because they lack the technology to collect the required information could face legal liabilities for failing to meet their sales tax obligations. States and localities will continue to miss out on some sales tax revenue. And without a framework in place, some revenue may be directed back to the seller’s location, rather than the buyer’s.

‘Extra Friction’ From Privacy Issues

When retailers sell and deliver physical goods, the street address is essential for getting the item to the customer’s location. With digital products, that information isn’t necessary from a business perspective, said Charles Maniace, vice president of regulatory analysis and design at Sovos, a tax compliance and regulatory reporting software publisher.

Certified service providers—agents certified to handle sellers’ sales and use tax functions—have collaborated with the states as part of Streamlined’s work group for years, but have been “fundamentally kind of stuck,” Maniace said.

“There’s a notion within the states that sellers and CSPs haven’t performed the necessary due diligence unless they’ve attempted to get from their customer their street address,” he said. States have “kind of staked out a position that it’s required” to perform tax compliance responsibilities.

Streamlined’s business advisory council has also said the proposed changes could discourage compliance among sellers who can’t meet the additional requirements and could conflict with state privacy laws requiring them to delete customer information.

“Some sellers aren’t configured to get, don’t get, and don’t want to get their customer’s street address for many reasons,” Maniace said. “For example, non-US sellers who until recently have been obligated to collect US sales tax, and have been dealing with tax systems where all you really need to know is the country.”

State consumer privacy laws can be and are amended regularly, said Melissa Krasnow, a partner at VLP Law Group in Minneapolis who advises companies on compliance with state, federal, and international privacy and data security. When lawmakers pass privacy laws they don’t necessarily think about how those measures could potentially affect state tax assessment and collections, she said.

“A state can clarify and say, ‘If you’re going to use this information for tax purposes, then it’s out of the purview of this competing or conflicting privacy law,’” Krasnow said. “I think that that’s a potential fix.”

Jeremy Grant, coordinator of the Better Identity Coalition, said the US still lacks an infrastructure, similar to one adopted in other jurisdictions, such as the European Union, where people can selectively disclose the personally identifiable information they need to provide.

“Unlike some other countries, we don’t have ways for Americans to selectively disclose things about them,” he said. “If we had that sort of infrastructure in place, the way we’re seeing other countries move forward with it, it probably would be a lot easier from a compliance perspective. But as it stands right now, some nuances could create potential legal and regulatory issues for some of the companies collecting the data while also generating extra friction that can slow down online purchases.”

Photo: Victor J. Blue/Bloomberg

Leave a comment